Motivating learners in learning: lessons from the implementation of competence-based curriculum in Rwanda

Following what UNESCO and World Bank call the “learning crisis”, global educational reform efforts have converged on improving the quality of education. One popular narrative is on shifting away from “teacher-centered” – a label associated with various negative connotations – towards “learner-centered” approaches that value students’ active participation in learning. This is commonly desired to ensure that students develop relevant knowledge and skills for the job markets among other national needs.

In Rwanda, reform efforts have come to form the Competence-Based Curriculum (CBC) implemented in 2016. While various issues about translating the curriculum objectives into classroom practices were already reported, similar challenges were also observed in other African contexts such as Kenya, Malawi, Namibia, Uganda and South Africa. The extent of curriculum implementation in African countries was conditioned by a wide range of factors. These include policy issues, material condition, teacher training, teachers’ perception, students’ academic and socio-economic background and parental support among others. Despite focusing on different schools and subjects, both of our fieldworks have engaged with teachers in Rwanda with specific interests in the teaching and learning process. We share a similar focus on understanding teachers’ perception of the reform, and the opportunities for pedagogical change in classrooms.

What did we learn from the implementation of Competence-Based Curriculum (CBC)?

During our fieldwork, promising signifiers of changes brought by CBC were observed. “Learner-centered” activities were used extensively to encourage student participation, such as through research-based activities, group work and presentation. Yet, the teachers we interviewed similarly shared several concerns around student motivation. For instance, some students were seen working separately despite sitting in groups. While this could be partially attributed to the nature of tasks assigned, some teachers pointed out that learning was still predominantly driven by national examination, rather than for learning itself or cultivating competencies. Some teacher trainers then highlighted the need for changing the learning culture. They observed that many student teachers remained dependent on lecturers’ delivery, rather than taking own initiatives to reflect on key points.

The extent of independent learning was further constrained by various factors. Notably, lingering challenges remain on English as the language of instruction, which is unfamiliar to many Rwandan teachers and students. Next, the prevailing large class sizes in public schools rendered the facilitation of every student difficult on top of classroom management. These were demanding circumstances for teachers who were already demoralised by the low welfare and salary. It was not rare to see reports about the substantial teacher turnover, and the shortage of professionally trained teachers. The scarcity of pedagogical resources also influenced the extent of student participation. As the majority of students did not own textbooks or other means to access ebooks, close-ended questions and notes-copying were essential lesson routines to ensure students memorize content well.

Widening access to remote-learning

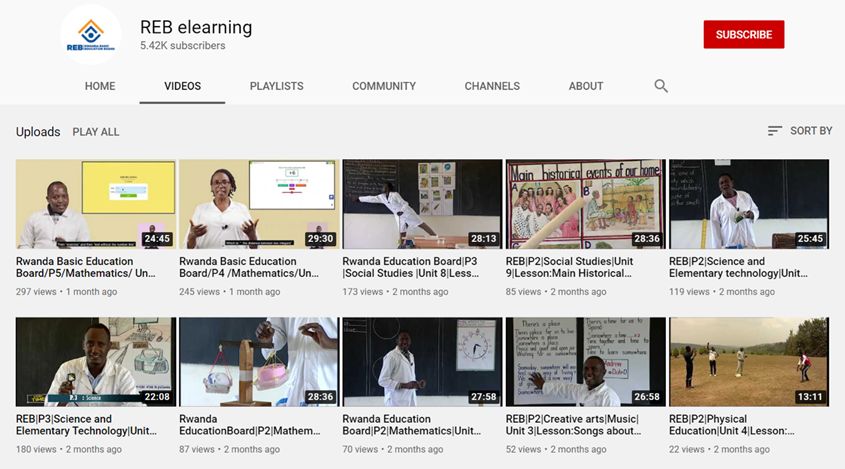

Learning opportunities during the global pandemic have relied further on student capacity and motivation. Since 15 March 2020, schools in Rwanda had been ordered to close. Swift responses were made by local authorities to minimize the disruption as per the learning plan set out by the Ministry of Education in “Keeping the doors open for learning”. Supported by Rwanda Education Board (REB), learning resources were uploaded online through multiple means. These include an e-learning portal, a Youtube channel, the national TV, and radio for students to continue learning independently.

While the abovementioned concerns remain, heightening worry was on the equitable access to these resources especially for underprivileged households and students with disabilities. Radio programmes and SMS-based learning were then assumed to play important roles in this regard. The Government of Rwanda was in collaboration with different partners such as the University of Rwanda-College of Education (UR-CE) and UNICEF to distribute free radio-receptors to low-income families. Meanwhile, the two major internet providers – Airtel and MTN Rwanda – also offered free internet to support learning. Yet, a recent study indicates that only half of the teachers interviewed managed to support students with remote learning during school closure. The major concerns for both school leaders and teachers, as raised in a local report, were related to student motivation.

Promoting a different learning culture

Rwanda is not alone with the challenges around adapting to online learning environments . Remote learning has put tremendous stress on teachers and students even in the most resourceful settings. As part of the burnout known as “Zoom fatigue”, across UK universities, students reported difficulties to stay motivated. Students doing online learning are found more likely to drop-out. Similarly for Rwandan teachers, they shared difficulties in following students’ well-being, individual circumstances, and responses in real-time.

In Nsengimana’s personal teaching experience at UR-CE, a widening learning gap was also observed. The participation rate remained low in both classroom sessions and online forums, except in quizzes which contributed to the final grades, and when the attendance was monitored. The value of online learning was still rather doubtful . In an instance of online assessment, although almost all students scored a full mark, such results did not corroborate with the final in-person examination. While this might suggest students completed the online quizzes “collaboratively”, some colleagues reported students using peer’s login credentials to obtain correct answers before completing their online tests.

These observations have led us to reflect further on the key enablers of “learner-centered” approach to education. In pre-COVID times, the importance of student interest in schoolwork was already reiterated by Rwandan teachers. The same concern is now further amplified in remote learning under COVID-19. Many students have to assist household chores among other income-generating activities. Given the compelling physiological needs, academic learning may no longer be the top priority for many.

Diversifying pedagogical strategies for the future

As uncertainties around COVID-19 remain, concerns about drop-out rates especially among underprivileged groups globally are alarming. Rwanda is also predicted to face similar challenges, in addition to a possible surge of repetition rates following the halt of automatic promotion. Hence, while infrastructure and teacher recruitment are important for reopening, the need for holistic support to students cannot be undermined. Apart from the mental health training set to be provided to teachers, a “school of excellence” has demonstrated an important initiative to support students as they enjoyed the new year celebration together. Such social bonding is invaluable for forming supportive communities of learners and teachers.

As asynchronous teaching continues to thrive, the pandemic offers a timely opportunity to revisit and develop a variety of teaching strategies. For instance, teachers’ role in facilitating learning in lessons is particularly significant where resources are not easily available or accessible by learners. Thus, lecturing can still be a crucial strategy, and does not necessarily carry the “chalk-and-talk” image.

Recommendations for future teacher training:

- Based on the contextual realities, the diversification of pedagogical strategies may be more helpful to achieve the goals envisioned in CBC, namely competences and higher-order thinking skills.

- It is important to stimulate student interest in learning even without the immediate presence of the teachers. Content, strategies, and examples in teaching and learning may consider including indigenous knowledge as well as those relevant to solving day-to-day problems.

- The language of instruction is a key enabler of participatory and independent learning. To further enhance classroom interactions, more strategies for multilingual CBC classrooms may be promoted, which is further supported by teaching resources.